The 30-60-90 Operations Playbook for Early-Stage D2C Brands

20-Jan-2026 permalink

There's a pattern I've seen across every D2C brand I've worked with — at Anveshan, P-TAL, Sleepy Owl, and now building FilFlo for dozens of brands. Between ₹1 crore and ₹10 crore ARR, operations becomes the binding constraint. Not marketing, not product, not fundraising. Ops.

At ₹1 crore, you can run things on WhatsApp messages, shared spreadsheets, and the founder's memory. The whole operation fits in your head. By ₹5 crore, that same approach is costing you 15–20% of your revenue in errors, manual reconciliation, and stockouts you didn't see coming. By ₹10 crore, it breaks outright.

The problem is that ops debt compounds faster than tech debt. With tech debt, you get slower deployments and frustrated engineers. With ops debt, you get missed orders, marketplace penalties, working capital locked in wrong inventory, and customers who never come back.

Days 1–30: Stop the Bleeding

The first priority is not building new systems. It's understanding where the current system is failing. Measure your fill rate. Audit your reconciliation errors. List every manual process that happens more than once a week. Stop maintaining four different inventory trackers — pick one source of truth even if it's imperfect.

The goal of month one is not optimization. It's visibility. You can't fix what you can't see.

Days 31–60: Build a Single Source of Truth

Month two is about getting your inventory picture right — actually right, in a system that updates in near-real time and that your whole team trusts. Centralize your inventory data. Rationalize your SKU catalog (your top 15 SKUs likely drive 80% of revenue — the rest is ops complexity you're paying for). Connect all your channels to one inventory pool with channel-level allocation logic.

Days 61–90: Make Ops Decisions Data-Driven

Set reorder points by SKU, not a uniform buffer for the whole catalog. Build a weekly ops review that takes 30 minutes. Automate your purchase order creation. Start tracking demand signals forward, not just backward.

The goal is an ops function that doesn't require your constant involvement to function — one that makes decisions daily without waiting for your attention.

Building ops infrastructure at an early-stage brand? I'd like to compare notes. Find me on Twitter.

The Festive Season Inventory Hangover: Why Indian D2C Brands Overshoot Every Year

12-Dec-2025 permalink

It's mid-December. The Diwali sale is long over, the Navratri gifting wave has subsided, and somewhere in a warehouse in Bhiwandi or Okhla, a brand is staring at three months of dead inventory it can't move without a 40% discount. Meanwhile, its best-selling SKU sold out on day two of the sale, leaving ₹30 lakhs in potential revenue on the table.

This is not bad luck. It's a structural failure that repeats itself so reliably you could set a calendar reminder. The same brands, the same mistakes, every year.

The Two Failure Modes

Stockout. You sell out of your best-performing SKUs within 48 hours. You scramble to replenish, but your manufacturer needs 10 days and the sale window is 7. You miss ₹X in revenue and your marketplace listing takes a visibility hit.

Overstock. You ordered 3x of everything "to be safe." Demand came in lopsided. Now you have 6 months of slow-moving inventory tying up working capital at exactly the moment you want to invest in January growth.

Why Gut-Feel Forecasting Fails Every Year

The typical festive planning conversation: "Last Diwali we did ₹80 lakhs. We're growing 40% YoY, so this Diwali should be ₹1.1 crore. Let's order for ₹1.3 crore to be safe." This is not forecasting. This is last year's number with a vibes-based multiplier and a buffer applied to cover the anxiety.

The problem isn't that founders are bad at forecasting. The problem is that they're using backward-looking data to make forward-looking decisions, without any mechanism to update as new signals arrive.

The right festive forecast is built from sell-through rates by SKU and channel, channel-level growth trends from the last two festive seasons, historical volatility by SKU, and early demand signals like pre-sale wishlists. Each channel's forecast should be built independently — not a top-down number split across channels.

The Fix: Build a System, Not a One-Time Plan

The brands that handle festive inventory well don't have better intuition. They have better systems. They've automated sell-through tracking, connected procurement lead times to order windows, and review SKU-level data monthly rather than quarterly. The festive plan becomes a data exercise, not an anxiety exercise.

The next Navratri is ten months away. That's actually plenty of time to fix this — if you start now.

Running into festive planning problems? I'd like to hear about them. Find me on Twitter.

Fill Rate: The One D2C Metric That Compounds Faster Than Revenue

10-Nov-2025 permalink

Most D2C founders I speak to can tell me their MoM revenue growth and their blended CAC within thirty seconds. Ask them their fill rate, and you get a long pause followed by, "We track that in a spreadsheet somewhere." That spreadsheet is usually three weeks out of date, maintained by whoever has time, and nobody acts on it until a marketplace flags a penalty or a retailer sends a nastygram.

Fill rate — the percentage of orders shipped complete and on time against what was promised — is, in my view, the single most consequential operational metric in consumer brands. Not the flashiest, not the one on the VC dashboard, but the one that determines whether you keep the shelf space, the relationship, and eventually the revenue you worked so hard to earn.

Why It Compounds: The 3-Stage Cascade

Stage 1 — Marketplace penalties. Amazon, Flipkart, and Blinkit all have fill rate thresholds built into their seller agreements. Drop below them and you get suppressed listings, held payouts, or outright suspension.

Stage 2 — Retailer delisting. Modern trade buyers at DMART or Reliance Smart have quarterly reviews. A pattern of partial fulfillments signals unreliable supply. By the time you notice, the damage is done.

Stage 3 — Brand trust erosion. A customer who orders your product and gets a partial pack doesn't complain. They just don't reorder. You see it as a cohort retention problem with a mysterious cause.

Fill rate is a leading indicator of revenue health. By the time it shows up as a churn problem, you've already lost six months of relationship capital.

Root Causes and the Fix

Fill rate failures almost always come down to three structural causes: SKU mismatches between systems (your ERP says 500 units, your WMS shows 480, the picker finds 460), procurement delays hitting order windows, and inaccurate demand signals driving wrong stock decisions.

If your fill rate is below 95%, start by auditing your SKU data across every system. Set fill rate alerts before penalties arrive. Map procurement lead times to your order acceptance policy. Build a 2-week inventory buffer by channel — not a blanket buffer, but channel-specific, because quick commerce demand spikes differently than modern trade delivery windows.

Sleepy Owl used this approach — connecting order management to real-time inventory and procurement timelines — to hit and sustain a 100% fill rate across their wholesale and marketplace channels. The goal isn't a perfect score on a single order. It's making 98%+ the default.

Thinking about fill rate in your ops stack? Let's talk on Twitter.

The Crucial Role of Systems Integration in Scaling Your Brand

20-Apr-2025 permalink

In the journey of brand growth, one of the most significant challenges brands face is the lack of integration between core systems like procurement, inventory, and invoicing. This integration isn't just beneficial—it's essential for sustainable scaling.

The Problem with Siloed Systems

When procurement is managed on spreadsheets and invoicing on standalone servers, the risk of errors increases dramatically. Manual data entry leads to discrepancies, resulting in overstocking, stockouts, or financial inaccuracies.

Without integration, each department operates in isolation, making it challenging to get a real-time, accurate view of the business. This leads to decisions based on outdated or incorrect data, significantly hampering growth potential.

The Impact on Scalability

As a brand scales, the operational overhead associated with these inefficiencies grows exponentially. This overhead becomes the limiting factor in growth, making it difficult to manage increased demand efficiently.

The lack of integration results in higher operational costs due to manual processes, errors, and the inability to leverage economies of scale. These costs can quickly become unsustainable as the business grows.

The Solution: Integrated Systems

Integrated systems automate data flow, reducing manual tasks, errors, and operational costs. This automation allows for real-time updates across all departments, ensuring that inventory levels, procurement needs, and financials are always in sync.

An integrated system provides a robust framework that can scale with your business. It ensures that as your operations grow, your systems evolve seamlessly to meet the demands, preventing bottlenecks and fostering sustainable growth.

With integrated systems, decision-makers have access to real-time, accurate data across all facets of the business, enabling agile responses to market changes and better strategic planning.

Real-World Example

Sleepy Owl Coffee's transformation through system integration with FilFlo demonstrates the power of this approach. They achieved:

- Streamlined PO fulfillment process

- Reduced operational errors

- 100% fill rate for orders

- Significant cost reductions

Key Takeaway

If your systems aren't designed to handle 10x scale, they're the ones that need dismantling first. Integration isn't just a technical upgrade—it's a strategic move towards operational resilience, cost efficiency, and the ability to grow without constraints.

Got thoughts on systems integration? Let's discuss on Twitter.

Links For Highly Ambitious People

24-Aug-2020 permalink

Back in college I used to spend a lot of time scrolling social media. I wish it was put to better use. Also, I am constantly amazed how ignorant I was to all the amazing opportunities on offer for students. So I am putting together a list of links worth spending time on.

Grants/Funding:

Summer Programs/Misc:

Other Fun Stuff:

General Advice:

- "Hell Yeah or No" - Article

- "How to Do What You Love" - Article

- "How to Maximize Serendipity" - Article

- Patrick Collison's Advice for Young People - Article

"The standard pace is for chumps."

Got any other links that should be on this list? Kindly email me.

Amara's Law

19-Jul-2020 permalink

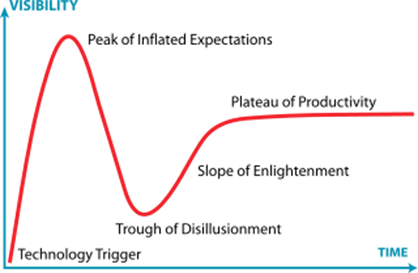

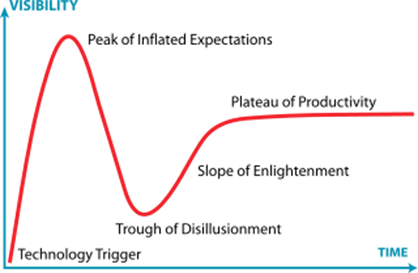

Predicting the future is a foolhardy exercise. The world is a complex system. Anyone who has studied complex systems knows that the cause-and-effect pattern-seeking human brain is incapable of processing nearly enough variables to make predictions of any value. Having said that, there is one law for predictions and trend-spotting that has stood the test of time. Albeit in the narrow field of application of a new technology. That is Amara's Law. It states that we tend to overestimate the impact that a new technology is going to have on our lives in the short run, but tend to underestimate it in the long run.

This has interesting implications for the technologies that are being talked about now (looking at you GPT-3). But first, let's go back in time to see how it applies to technologies that were invented in the past.

First, the internet. We are all familiar with the dot-com bubble of 2001. It came on the heels of seemingly boundless growth of Silicon Valley startups, flush with investor money, promising to solve all of humanity's problems, only to be followed by a crash destroying $5 trillion in market capitalization of stocks in the process. The eager venture capitalists, the irrationally exuberant founders, and the opportunist Wall Street traders were all victims of Amara's Law.

The technology had not matured yet, the market had a limited number of people who could access the internet, and so on. The inflated expectations did them in. Amara's Law doesn't just trap people on the peak of inflated expectations but also in the trough of disillusionment. Around the same time, the Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman wrote that "by 2005 or so, it will become clear that the internet's impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine's." He went on: "As the rate of technological change in computing slows, the number of jobs for IT specialists will decelerate, then actually turn down; ten years from now, the phrase information economy will sound silly."

The internet is probably asking, "Who sounds silly now, Mr. Krugman?"

The same pattern can be seen if we go further back to the invention of the steam locomotive in 1802. Electricity, automobiles, personal computers—same thing. The law can be explained by some combination of the Dunning-Kruger effect and René Girard's Mimetic Theory. But I won't get into that here.

Amara's Law is currently unfolding for artificial intelligence and at a much earlier stage for blockchain technology. Over the last decade, both have become buzzwords on startup pitch decks. AI has started predicting travel times accurately only recently. This suggests we are slowly climbing the plateau of productivity for AI. For blockchain, I feel we are squarely in the middle of the trough of disillusionment, after the 1 BTC = $20K peak for Bitcoin in late 2017.

Why Stoicism Matters

25-Oct-2018 permalink

Most famous philosophers were polymaths, among the handful of geniuses of their respective generations. Their work often dealt with either building on or deconstructing the work of their predecessors. When we iterate this process over thirty generations of polymaths, we get the current state of philosophy. Much of philosophy is, therefore, abstract and complicated. It is so divorced from daily life that only a handful of graduate students care about it anymore. It deals with solving pseudo-intellectual problems, but hey, isn't that what most of academic life is like these days?

Philosophy wasn't always this way; it used to be about helping people live their daily lives and find the appropriate path to follow. That is where Stoicism comes in. Stoic ethics can be thought of as a means of protecting ourselves from any external adversity that can possibly be thrown our way. The most famous philosophers from the school of Stoicism were Marcus Aurelius, who was a Roman emperor; Seneca, who was the teacher of Nero; and Epictetus, who was born a slave. I will be discussing ideas from the works of this trio, also known as the "crown jewels" of Stoicism, in this article.

Things that you are going to learn from this article are going to be directly applicable to whatever challenge you are facing right now. Don't take it from me; take it from these guys. Seneca was Machiavellian fifteen hundred years before Machiavelli was born. He amassed wealth and was not without flaws. When he called in one of his loans from the Roman colony in Britain, it collapsed their economy and sparked off a rebellion. Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett's number two at Berkshire Hathaway, is a Seneca fan and quotes him often. Oil and gas billionaire Thomas Kaplan funds a course on Stoicism at Brown University. The list goes on to include names like Theodore Roosevelt, Bill Gates, J.K. Rowling, and Arnold Schwarzenegger, who are all fans of Stoicism.

At this point, you are probably thinking, "Yeah, alright, alright, alright. I see Stoic ethics can be useful, but what are they?" Let's get right down to answering that query. Here is a list of things you can do to add more Stoicism to your everyday life:

1. Overcome Emotions

Stoics love to separate all things into two categories: things we do control and things we don't control. The things we do control are our thoughts and actions. The things we don't control are...well...everything else. Too often, humans are guilty of letting their emotions decide the course of their thoughts and actions. The idea is that we should not get carried away by "passions" of desire, pain, pleasure, and fear. All of us feel these emotions, but the Stoics try to act out of reason. Therefore, they feel the emotions but choose to respond in a way that they think is best.

Now, the first thing to get out of the way is the misconception that Stoicism is about suppressing one's emotions and going through life with a stiff upper lip. The modern image of a Stoic is that of an unemotional and feeling-repressing person. This is definitely not what it originally meant. It's not what Stoicism is about.

Some could even say that this clampdown on their emotions is an impediment to their expression of free will. To those, I would argue the exact opposite. When we act in accordance with our emotions, we are doing just that. We do not allow our ability to reason or wisdom to change our course of action, letting emotion overrule everything. The Stoics are not without emotions. If it were so, then there would be no emotions to overcome. They do have feelings, but they are not enslaved by those feelings.

"Right, no one said anything about not feeling it. No one said you can't ever cry. Forget 'manliness.' If you need to take a moment, by all means, go ahead. Real strength lies in the control or, as Nassim Taleb put it, the domestication of one's emotions, not in pretending they don't exist."

— Ryan Holiday, The Obstacle Is The Way

Overcome your emotions; don't pretend they don't exist.

2. Get Out of Your Comfort Zone

Today, we live amid a 'swipe-right' generation. Enabled by technology, we have built systems that allow us to get instant gratification. We have surrounded ourselves with a setup that is designed to save us from getting out of our comfort zone. Don't like the food you are eating? Fine, just install an app and order whatever you like. Don't like the job you are doing? Fine, just install an app and get a new one. Don't like the person you are dating, home you are staying in, or heck, the phone you are using? Fine, just install... you get the idea.

Now, don't get me wrong here; these new-age systems are an absolute joy to use and remarkably convenient too. Mini dopamine bombs delivered right into our comfort zones. But all this has come at a cost. 'Instant' is the only kind of gratification that Generation Y and Z know. Imagine the satisfaction and happiness one would feel in putting food on the table after a long day of toiling in the field. Now, to put food on the table, you can just go to your boring job for eight hours. We feel no gratification in having that food.

In trying to make our lives easy, we have eliminated our struggles. Now we just find it hard to stick with something we are struggling with. This, in simple terms, disables us from getting the satisfaction which we would have gotten as a result of the struggle. Not only that, going out of our comfort zones and getting our hands dirty also helps us in cultivating mental resilience. This makes for a cool transition to my next point.

La Masia, Barcelona Football Club's youth academy, has produced hundreds if not thousands of professional footballers who play in top leagues all around the globe. According to them, the best indicator of the success of a teenage player as a professional is neither their skill with the ball nor their ability to see passes or their athleticism. Rather, the best indicator of success is mental resilience, and this is true in a number of professions.

To build resilience, the Stoics advocated measures which could be broadly described as 'voluntary discomfort', including steps such as sleeping on the floor and practicing poverty—definitely off-brand in 2018. The idea is that once we overcome the need to feel comfortable at all times, we will find it easier to stick to our plans and find ourselves capable of grappling with obstacles.

3. Love Your Fate

Stoics were determined champions of acceptance. They often called it the "art of acquiescence"—to accept rather than to fight every little thing. Strikingly similar to Nietzsche's concept of "Amor Fati", which is Latin for "the love of one's fate", asking us not just to accept our fate but to love it. It is a very powerful idea.

To understand this idea, consider an example of a dog leashed to a cart. The dog represents a person, and the cart represents his or her fate. Now, the dog can either walk willingly and avoid getting pulled by the leash, or the dog can fight and get pulled by the cart unwillingly. Regardless of what the dog decides to do, the cart is going to pull the dog to wherever it goes. The dog tied to the cart is a metaphor for life itself, where we are the dog and the cart is our fate.

"My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it—but love it."

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, section 10

The author talks about Amor Fati like it's some sort of magic power, almost as if it can only be achieved after arduous struggle. Amor Fati is a mindset that we can take on to make the best out of everything, treating every challenge as something to be embraced, to not just accept fate for what it is, but to love it, converting challenges and adversity into fuel for our potential.

"Fate leads the willing and drags along the reluctant."

— Seneca